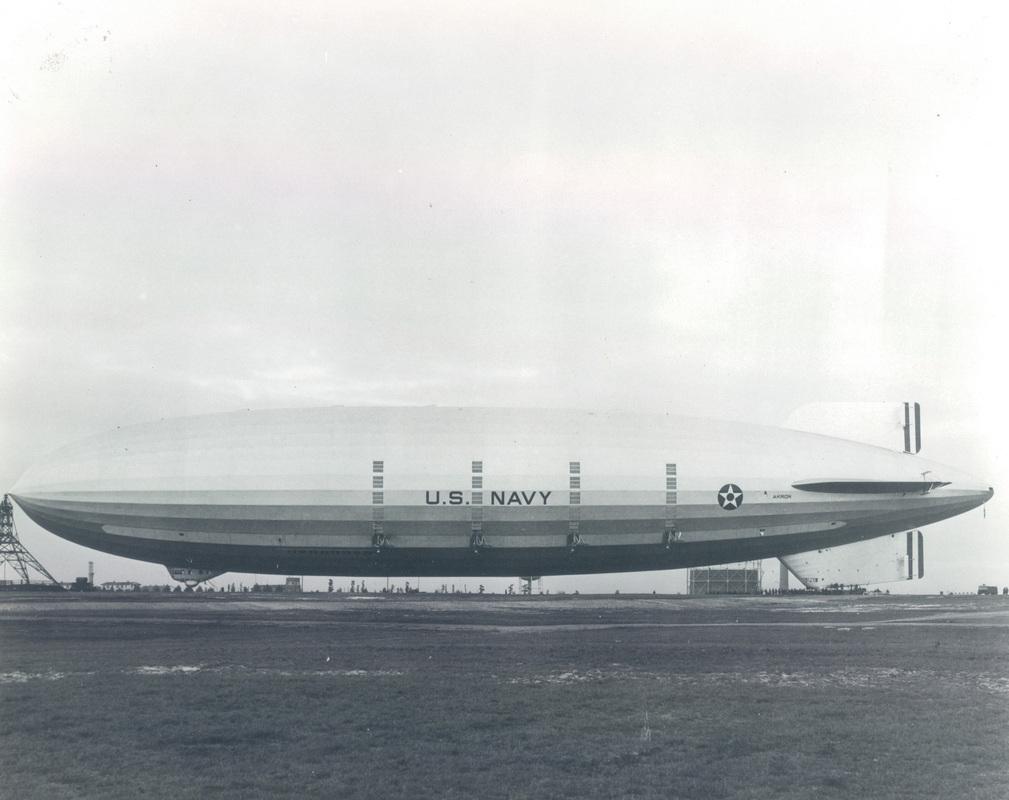

The first of the two was the USS Akron.

The ACRON ZRS-4 and the MACON ZRS-5 carried small scout planes called sparrow hawks. Watch this video to see the Akron in action.

Design and Construction

Following the loss of the ZR-1, Shenandoah, in September of 1925 the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics, with Admiral William A. Moffett as its chief, recommended a comprehensive program of rigid airship development. This plan called for the construction of two large rigid airships and a West Coast LTA base. The navy’s General Board was less enthusiastic, however, and when the matter was referred to them they recommended only one rigid airship, and only if the funds were provided outside the navy’s normal appropriations.

This token nod to the rigid airship was unacceptable to Admiral Moffett who in response had a House bill introduced which called for a replacement ship for the Shenandoah built with funds from the regular navy budget. Congressional hearings followed and resulted in the navy’s Five Year Aircraft Program, which included authorization for two large rigids, becoming law on June 24th, 1926. Appropriations, however, were not made available until 1927. In that year design submissions for a large rigid airship scout were requested. The winner of the competition was Goodyear-Zeppelin’s entry.

Coincidentally with the construction of the LZ-126, Los Angeles, for the U.S. Navy, the Zeppelin Company’s head Dr. Hugo Eckener entered into an agreement in October 1923 with the Goodyear Corporation. Under the agreement the Goodyear-Zeppelin Company of Akron, Ohio, was to be given North American rights to the Zeppelin Company’s patents as well as key Zeppelin personnel to bring the Zeppelin Company’s long experience in rigid airship design and construction to the New World. In exchange, the Zeppelin company was given ten percent of Goodyear-Zeppelin’s stock and the knowledge that no matter what the Zeppelin Company’s future would be in the uncertain economy of post-war Germany, the rigid airship would have a future.

The noisy protest of the American Brown Boveri Electric Corporation, however, caused another competition to be held in 1928, but the result was the same. Goodyear-Zeppelin, under the direction of Dr. Karl Arnstein, one of the thirteen key personnel of the Zeppelin Company sent to America, had created an innovative design for the largest airship yet constructed.

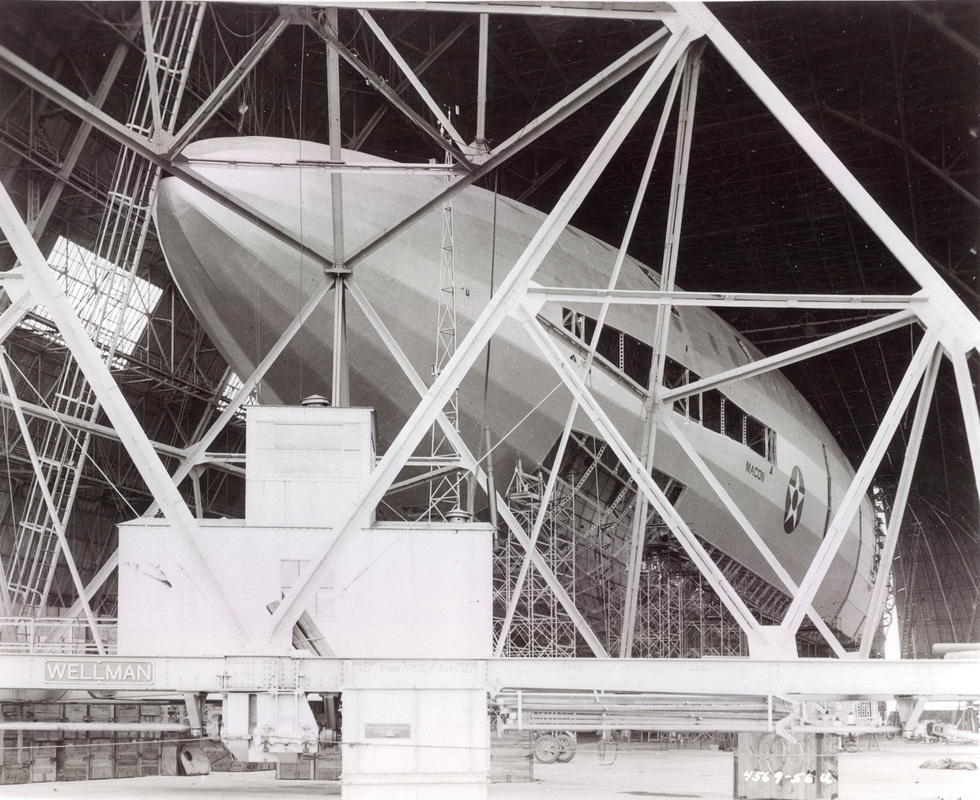

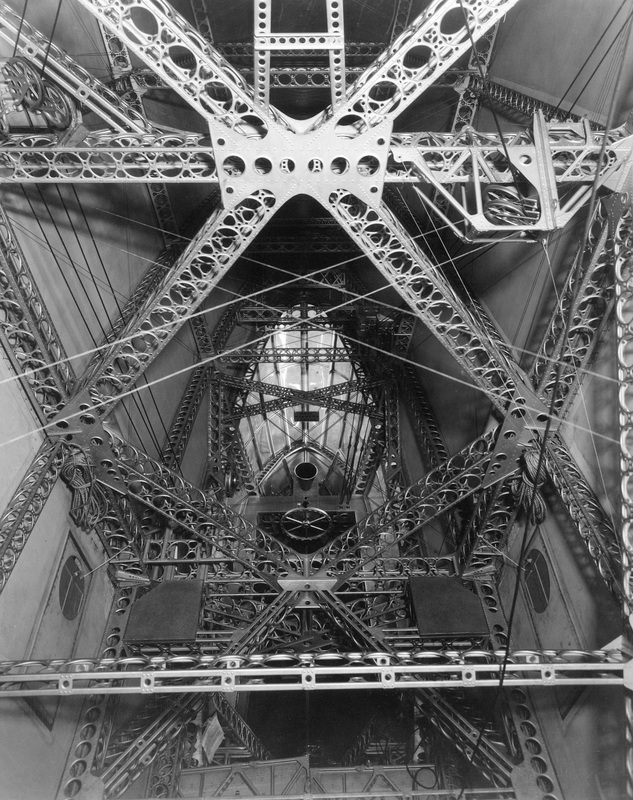

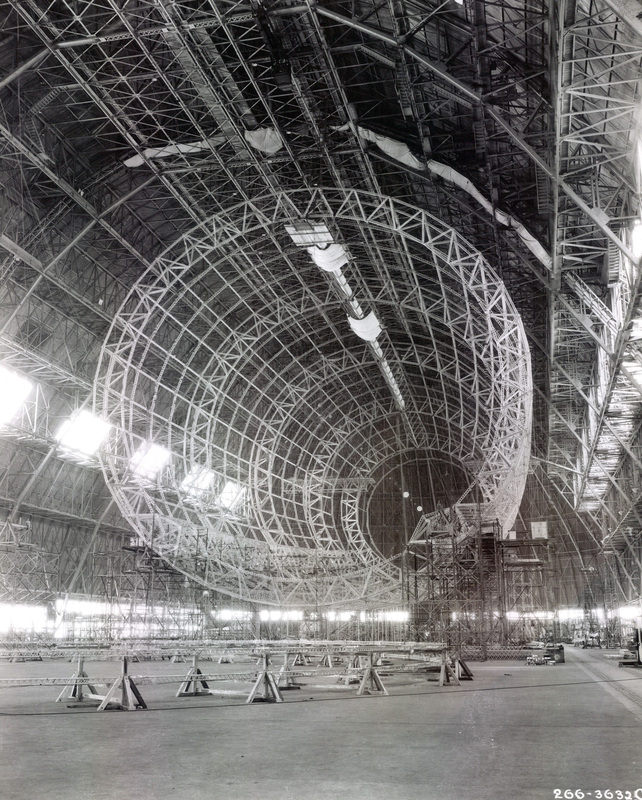

Goodyear-Zeppelin’s design called for a ship of 6,850,000 million cubic feet, 785 feet long with a maximum diameter of 132 feet, 11 inches. The ship was full of innovations. Rather than standard Zeppelin main rings, the ship had much sturdier deep main frames which dispensed with the miles of radial wiring which reinforced the Zeppelin main frames. In addition, the ship had three keels, as opposed to the one which had been standard up to that time. One keel was placed along the top of the ship, with the remaining two 45º below the horizontal. These provided unparalleled access to all parts of the ship as well as tremendous strength. The lessons of the Shenandoah and R-38 had been well learned.

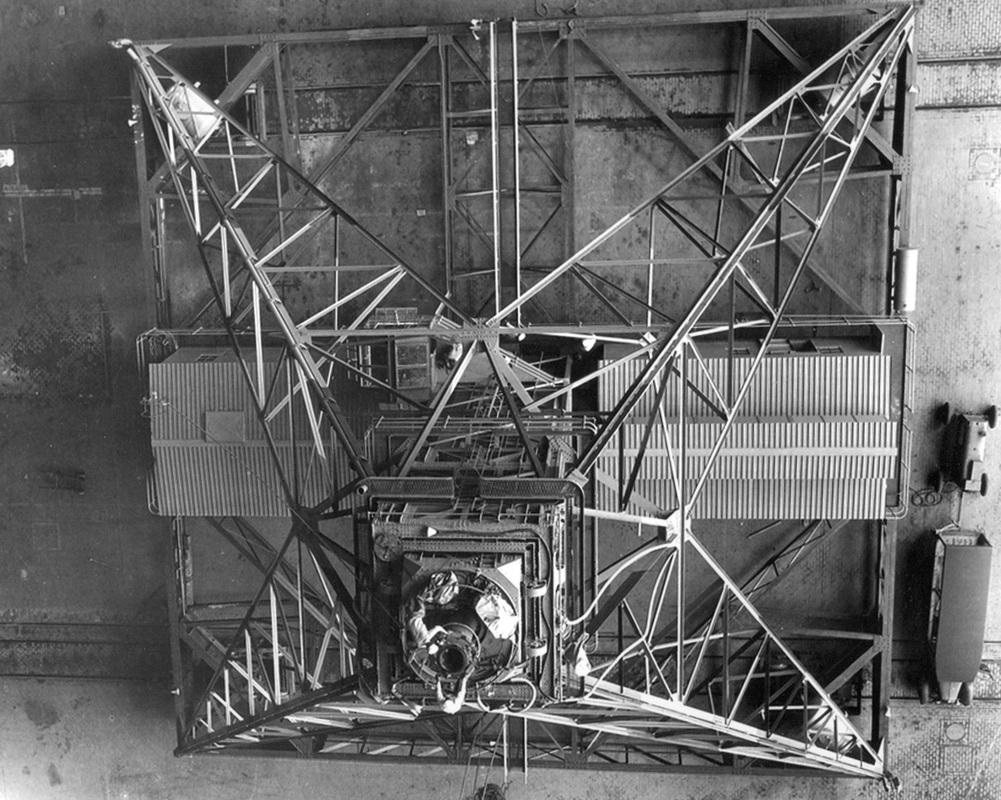

The most innovative feature of this design was the ability of the airship to launch, retrieve, and service five aircraft for scouting purposes. Approximately one-third of the way aft was an internal hangar, approximately seventy-five feet long, sixty feet wide, and sixteen feet wide. Through a T-shaped opening in the floor of the hangar a trapeze could be lowered onto which the ships five airplanes could be launched and retrieved from “sky hooks” attached to the top of the airplanes. Operating as the airship’s eyes, these scout planes extended the scouting area tremendously. More importantly, they

allowed the vulnerable airship to remain far from an enemy’s carrier based fighter planes.

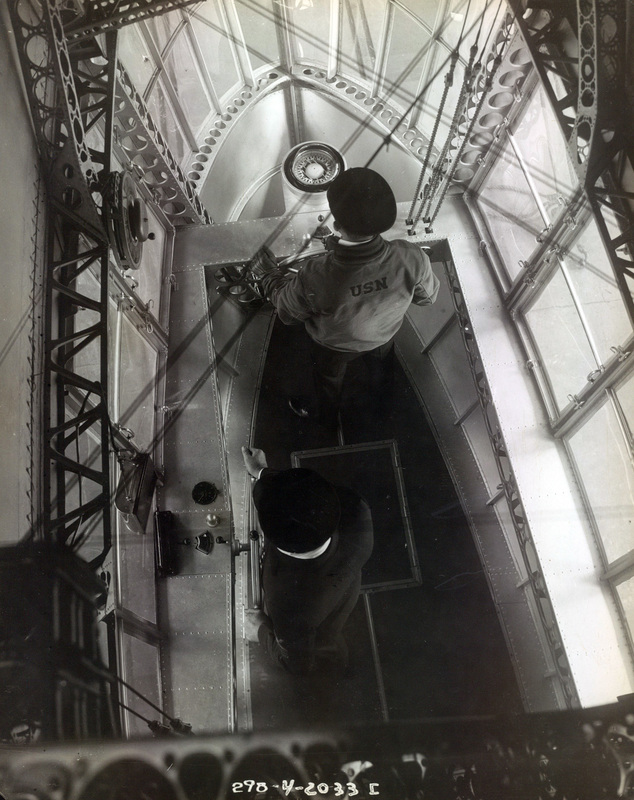

The crew’s quarters were on either side of the airplane hangar and included a mess, galley, washroom, and sleeping quarters for both officers and enlisted men. The crew’s quarters were heated by the cooling water from the engines, a first in rigid airships. A small control car was built into the hull fore. An emergency control station was provided in the lower fin.

Because the ship was designed from the outset for inflation with nonflammable helium-a gas which then only the U.S. had in quantity-the ship’s eight 560 hp Maybach VL-2 engines were installed within the hull along the two lower keels. They each drove a propeller at the end of a sixteen foot outrigger. As the engines were reversible and the

outrigger could swivel the propeller through an 90 degree arc, thrust could be delivered in any direction for aiding landings.

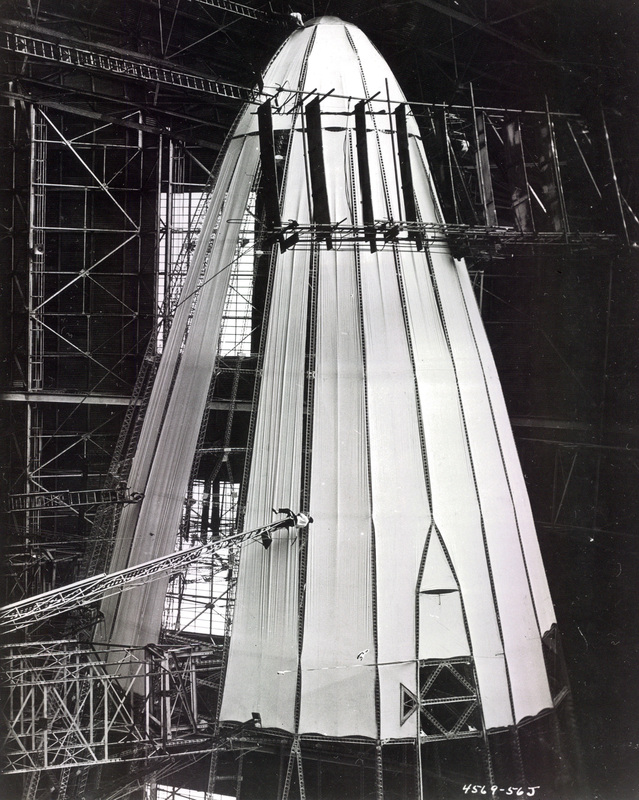

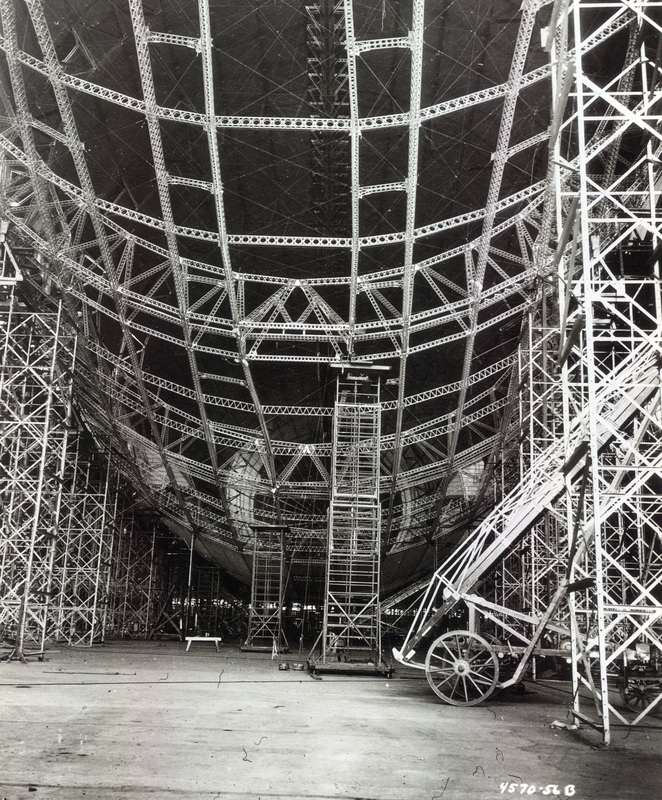

Construction of the new ZRS-4, later christened the Akron, began on November 7, 1929 at the new Goodyear-Zeppelin Airdock in Akron. Assembly was similar to that of other airships. The main rings were assembled on the floor of the hangar and hoisted into place then connected by longitudinals. The exterior of the airship was then covered with cotton fabric and doped.

Several small changes were requested by the navy, but only one significant. This involved the fins. In. Dr. Arnstein’s original design the ships fins were long and slender, attached to three of the ships main frames. However, this design would not allow the captain in the control car to see the lower fin and check his ship’s trim. Thus a design change-Change Order No. 2-was made, shortening and deepening the fins and moving the control car back eight feet. As a result the fins were now only attached to two main frames. The new fins also negated the design loads figures, which were later found to be too low. However the navy opted to leave the design unmodified.

By late summer 1931 the Akron was complete, and was christened on August 5. On September 23rd, with Lieutenant Commander Charles E. Rosendahl in command the Akron took to the skies for the first time.

USS Akron: A New Home at Lakehurst

On September 23, 1931 the Akron lifted off from the Goodyear-Zeppelin airfield at Akron, Ohio on its maiden flight. This flight was the first in a series of ten test flights which totaled 124 hours 11 minutes. These test flights included a thirteen hour flight to her home base, the Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey, where she arrived at dawn on October 22 and was brought into Hangar Number One next to the Los Angeles. One week later the Akron was commissioned as a vessel in the United States Navy.

At Lakehurst the Akron’s arrival was the culmination of several years work. Since the contracts were signed for the Akron and her yet to be constructed sister ship in 1928 activity at the base had increased precipitously. Men would have to be taught to fly the new airships, so training at Lakehurst increased accordingly. By the time the Akron arrived at Lakehurst there were some three hundred enlisted men and twelve officers, including base commander Captain H. E. Shoemaker, assigned to the base, plus seventy enlisted men and twelve officers of the Los Angeles. The Akron brought with her an additional seventy-five enlisted men and sixteen officers, plus her airplane pilots and mechanics. The many men at Lakehurst had done much work in anticipation of Akron’s arrival.

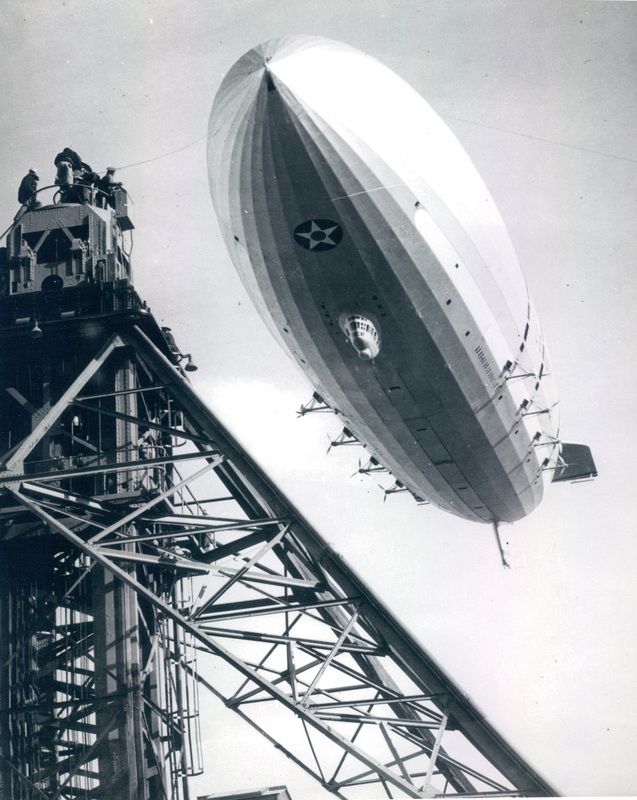

When the navy acquired its first rigid airship, the ZR-1, Shenandoah, docking and undocking was accomplished by assembling hundreds of men to “walk” the ship into and out of the hangar. While improvements in ground handling had been made with the Los Angeles, a dramatic improvement would be needed for the great new airship.

The system which the navy developed was a complicated but successful one. To move the ship into and out of the hangar, the nose was attached to a low mast which rode on two pairs of rail road tracks. The lower fin of the ship was then attached at reinforced points to a stern or “Bolster” beam, so named for its inventor, Lt. Calvin Bolster (CC). The stern beam resembled a long flat car. It weighed eighty-five tons and ensured that the ship remained well controlled as she was entering and leaving the hangar. The mobile mast and stern beam were attached by flexible connectors.

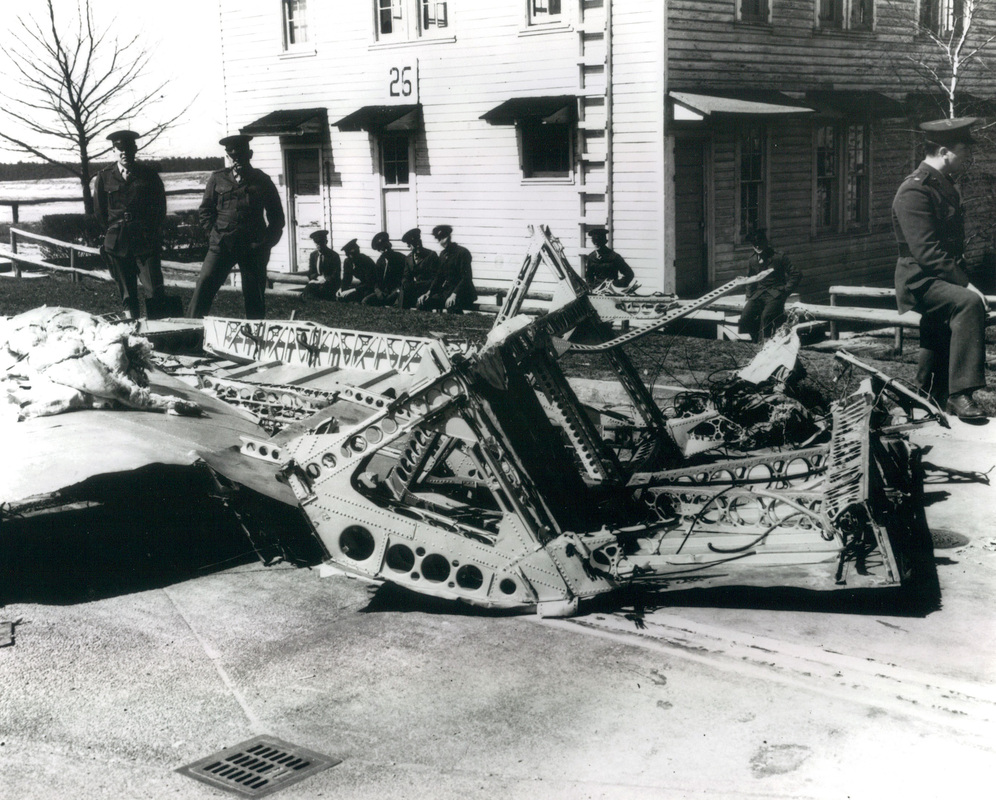

When the ship left the hangar at Lakehurst it was brought to a “hauling up circle” just outside the western doors. There the ship’s stern was moved by a small locomotive so that the ship faced into the wind. With the ship pointed into the wind the stern beam was removed. She was then brought to the “mooring out circle” farther from the hangar where the ship could weather-vane into the wind on a taxi wheel on the lower fin. From the mooring out circle the ship could safely depart. The system worked well, and there was only one major incident, in February 1932, when the lower fin broke free of the stern beam and weather-vained into the wind, banging into the ground several times.

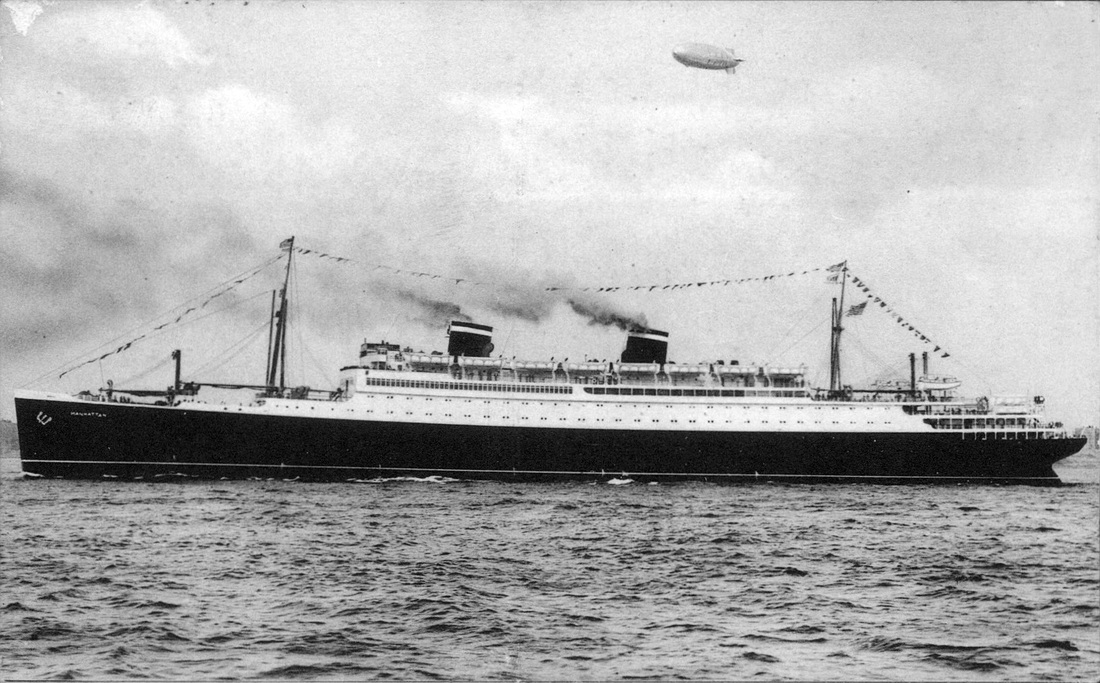

With the navy now in possession of a large, modern rigid airship specifically designed to act as a naval scout it seemed that the lighter than air was about to prove its tremendous value for scouting. On November 2, 1931, Akron made her first flight as a commissioned vessel in the U. S. Navy, a round trip flight to Washington with Admiral Moffett and a group of journalists aboard. The next day the Akron made a short demonstration flight to show the large rigid’s ability to carry out emergency airlifts. She carried 207 people aboard and set a world record. While these public relations flights did help to improve the public’s opinion of rigid airships, they did little to impress the rest of the navy. To do that the Akron would have to prove herself with the fleet.

Her first chance to do that came in January 1932. On the ninth she departed Lakehurst for Cape Lookout, North Carolina where she had orders to be at dawn on the tenth. That day she was to search for an “enemy” consisting of a squadron of destroyers. Despite passing within fifteen miles of the “enemy” she failed to spot them on the tenth. Resuming her search again at dawn on the eleventh she soon found the destroyers and was shortly thereafter released from the exercise.

The Akron’s lackluster performance did not impress the rest of the navy, but it should not have come as a surprise. The Akron had as of yet no airplanes; indeed she didn’t even have a trapeze from which to launch and retrieve airplanes. This constituted a serious handicap. Due to equipment delays and the damage sustained to the Akron’s lower fin in February it was not until July that the Akron’s HTA (heavier-than-air) unit was fully operational.

This delay did have some advantages. Hook-on experiments with the Los Angeles had been going on for some time and were now considered quite routine. Thus when the Akron’s airplanes arrived there were very few problems. Indeed, it was the consensus of the airplane pilots that a landing to a trapeze was easier than a conventional landing.

The arrival of the HTA unit highlighted the differences of opinion as to how airships should be handled. The HTA pilots believed that the large rigid was vulnerable to attack by an enemy’s carrier-born airplanes and, therefore, the Akron should serve as a flying aircraft carrier. Her airplanes would do all the scouting while the airship kept away from the enemy. The officers and crew of the Akron believed otherwise. In their opinion the Akron was a scouting airship which happened to carry airplanes, primarily for defense. Experience was to prove the HTA pilots correct in their evaluation.

On May 8, 1932 the Akron departed Lakehurst for California with two airplanes, the XF9C-1 and the N2Y. Neither were particularly suited to scouting, but the Akron would have to make do. On May 11 the Akron landed at the auxiliary base at Camp Kearney, near San Diego to land and refuel. She then headed to the still incomplete air station at Sunnyvale.

Most of her flights in California were public relations flights to satisfy the great demand for views of the ship. The ship did make some flights with the fleet, however. Between June 1 and 4 Akron took part in fleet exercises. Again she had no airplanes. The Akron found the “enemy,” but this time the “enemy’s” cruisers responded by attacking the Akron with their seaplanes. The Akron was “shot down” multiple times. The Akron’s commander, Charles Rosendahl, thought it “perfectly apparent” that had she had her planes aboard the Akron could have fended off the attackers. Perhaps he was right, but the Akron’s poor performance did nothing to polish her dull image. The report on the fleet exercises heaped harsh criticism , albeit criticism from a bitter critic of the airship, Adm. Frank H. Schofield. The Akron arrived back at Lakehurst on June 15.

At Lakehurst on June 22 Comdr. Alger H. Dresel relieved Rosendahl as commander. At the same time Comdr. Frank C. McCord reported to the Akron for duty under instruction as her prospective commanding officer. On January 3, 1933 McCord became the Akron’s commanding officer. The same day Akron departed for the expeditionary mast at Opa-locka, near Miami, Florida. While there the ship made a quick trip to Cuba. The purpose of this trip, and another to Panama in March, was to explore the possibility of a winter mooring site for the Akron away from the Northeastern winters. The consensus was that such a site would aid the Akron greatly, allowing it to fly more during the winter.

On the evening of April 3, 1933, the Akron departed Lakehurst for a routine training flight. There was nothing in the weather forecast which would indicate trouble. It was with no sense of apprehension that the Akron cast off at 7:28 P.M. Yet within hours the ship had been enveloped in a severe cold front. McCord had the ship turned east to ride out the storm at sea off the New Jersey coast. Just after midnight the air became quite turbulent and the Akron was carried downward. Drooping of emergency ballast fore and full speed on all engines stopped the descent at seven hundred feet. The Akron soon returned to its cruising of sixteen hundred feet. Two to three minutes later the Akron was caught in another down draft. With the altimeter reading eight hundred feet the ship lurched sharply, as if a strong gust had hit it. The rudder man then reported no response from his wheel. The men in the control car braced for impact with the ocean. Wiley, the only survivor from the control car, saw the waves below him and was washed out of the control car moments later.

There had been no impact of the lower fin with the sea before the control car hit the ocean. The reason for this apparent anomaly was that the fin was already in the ocean. The lurch which all had assumed was a gust, and which the altimeter would seem to insist was just that, was actually the lower fin hitting the water. No one realized the severity of the low pressure system through which the Akron was flying. The low caused her barometric altimeter to read as much as several hundred feet higher than the actual altitude. The Akron had literally been flown into the sea.

The Akron carried no life jackets and only one rubber raft. Most men never got out of the foundering ship, and of those who did only three survived exposure to the chilly north-Atlantic waters. Seventy three men perished. The tragedy was compounded the next day when the blimp J-3 crashed while looking for survivors, going down with two members of its crew. The navy had lost the finest airship in the world and seventy-five men. It was the beginning of the end for naval lighter-than-air.